When Alexander the Great led his armies into Persia, he burned his ships, destroying their only point of retreat. The message was clear: we win, or we die.

Guess what, they won.

Modern sensibilities tend to reject this attitude towards success. It’s not just about the goal, it’s about how we achieve the goal, and how it fits in with everything else. Let’s lean into this and take a look at our first theory: plot and life.

Theory # 1: Plot and life

The idea here is life can be understood as a story, and we can navigate this story with two signals: Whether a particular action advances the plot, and whether it feels alive.

Advancing the plot

Plot, in this context, is story arc we’re consciously moving through: a series of events, involving a cast of characters, animated by theme, oriented towards a goal. A plot is more than just a goal, but goal is indispensable to plot—they all have a teleology.

You usually know what plot you’re in, or else, you can figure it out. Start by identifying your goal, and the story and context around it. If nothing comes to mind, it’s possible you’re in a plotless story. If you find yourself coming up with a bunch of goals and attendant contexts, you may be in a story with multiple plots.

There are many ways an action might advance the plot. Maybe we take a direct step towards our goal. Or a lateral step which makes the goal more likely over time. Maybe we connect more deeply with the characters involved in the plot, or enhance our understanding of the plot’s themes.

Any action which builds out the plot and keeps it moving forward (in the general direction of the goal) advances the plot.

Aliveness

The second signal is aliveness, and it’s less a structure than a feeling, along the lines of “feeling right.” Aliveness can manifest in various ways:

Being interested in a book

Getting into a flow state with creative work

Being captivated by a new person

Feeling deeply connected to arc of life, awed by its power and beauty

Some have described aliveness as what happens when you vibe with your true self. Aliveness signals that something matters to some part of you, likely a part beneath the level of conscious articulation. And this model makes the assumption that this mattering is, on balance, worth paying attention to.

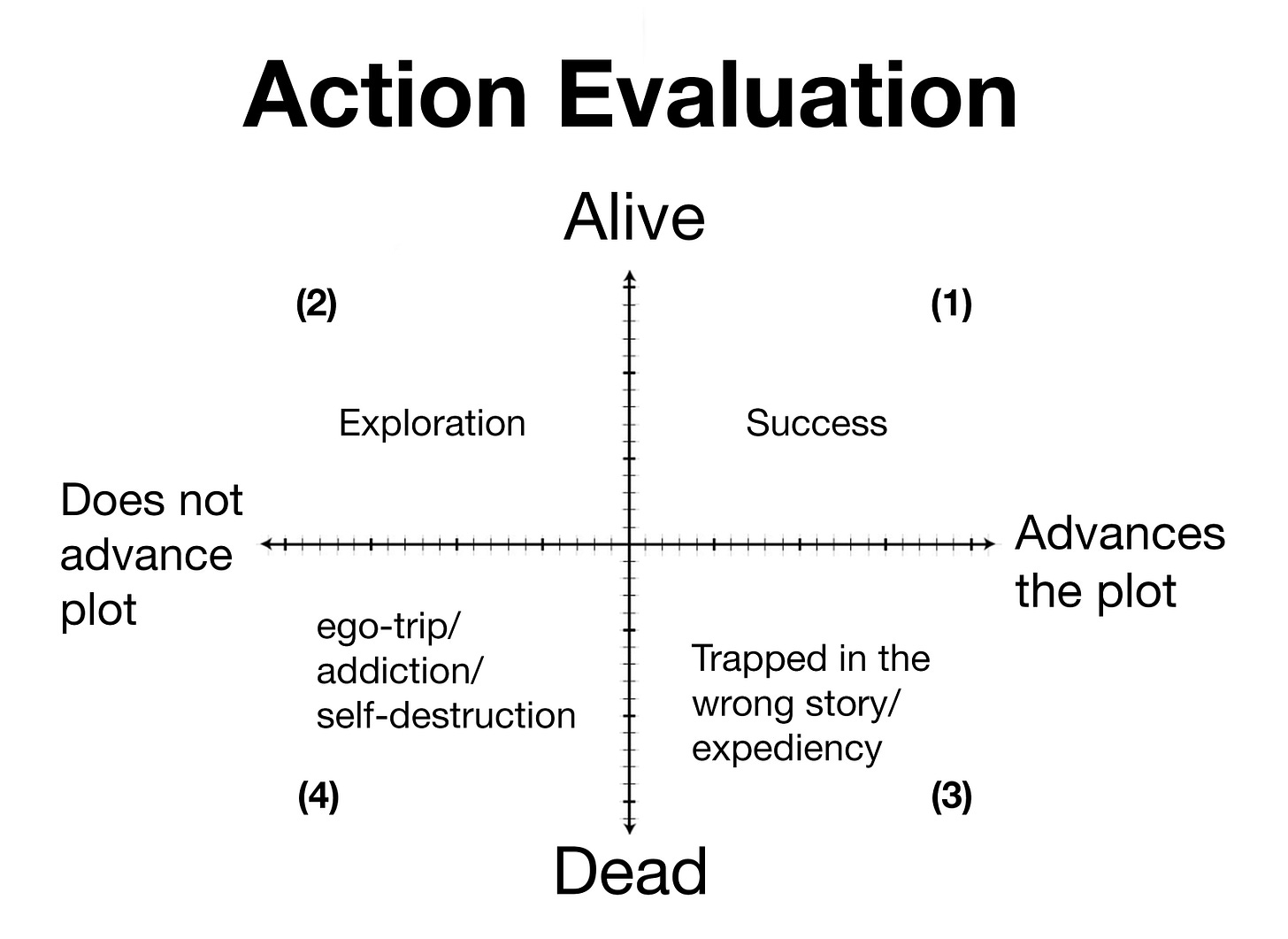

So we’ve got two axes: the degree to which an action advances the plot, the degree to which it feels alive.

This model divides action into four quadrants:

(1) Success: actions which feel alive and advance the plot

(2) Exploration: actions which feel alive and do not advance the plot

(3) Expediency/plot death: actions which feel dead and advance the plot

(4) Self-destruction: actions which feel dead and do not advance the plot

It’s clear that (1) is an excellent place to be—moving through the right story, with the right people, at the right place and time. But the others aren’t necessarily bad—at least not (2) and (3). Signals from quadrant 2 (exploration) are important in selecting the right plots, navigating between plots, and building new ones.

Quadrant 3 (advances plot and dead) is also important—where quadrant 2 is the birthplace of new plots, quadrant 3 is where plots go to die. If we find ourselves here, it’s a sign we’re living the wrong plot. Alternatively, we might just need to spend time doing something longterm-important but deadening: boring aspects of work, like spreadsheets or data entry. If we’re tuned in deeply enough, these actions might feel alive despite their tediousness, but that’s not always the case.

And we arrive at quadrant 4—feels dead and does not advance plot. This is the domain of shadow—addiction, ego trips, self-destruction, all the ways we sabotage ourselves.

When applying this framework to my own actions, I found that a common pattern was a combination of quadrant 1 and 4. I’d be doing something on-plot, which felt alive, but I’d veer into some bad habit: show up for my good deed hours late, initiate an important conversation only to get angry and snap. When we try to do the most meaningful, alive, and difficult things, it can bring out our worst—and maybe that’s necessary. The purpose of pursuing success isn’t just to achieve the object of success, but to clear our shadows.

As this model makes clear, life isn’t merely about achieving our goals: it’s about tuning into the larger story, becoming better people, learning, growing, navigating the beautiful, holistic, deeply felt tapestry of this mysterious existence.

Theory #2: Burn the ships

But what if I don’t care about the journey and the lessons and the friends we met along the way?

What I just want to achieve my goals? Become rich and famous? Triumph over my enemies?

Fuck modern sensibilities. Let’s burn the ships.

The idea of Theory 2 is to set high stakes. Imagine failure conditions as catastrophic and painful. Alex Hormozi, a billionaire YouTuber, suggests imagining that your family’s been kidnapped, and will be murdered if you fail.

Better yet, set up your life so failure truly is catastrophic. Quit the day job and go all in on the dream. Sell everything and move to the place you’ve always wanted to live. Get married without a prenup.

Studies show this works: when people are encouraged to create Plan B’s, their chances of success at Plan A decreases.

Let’s break it down why this works:

Burning the ships creates a Point of No Return: In most battles, there are always some deserters. Burning the ships makes abandoning the goal impossible.

Burning the ships makes you ruthless. Studies of soldiers found that most don’t shoot to kill. Burning the boats forces you to do whatever it takes.

Burning the ships projects fearsome determination. When others see you’re all in, they’re inspired to believe in your cause.

Burning the ships puts pressure on the commander. Caesar’s “crossing the Rubicon” was a burning of the ships for himself alone—he’d committed a capital offense, and would’ve been executed if he failed. Burning the ships unites the forces and forces commitment to the best possible plan.

Plan B’s are distracting, and they’re psychologically softening: if the cost of failure is another decently okay plan, that’s one thing. If the cost of failure is disaster or death, that’s quite another.

Which model to choose?

My friends advocate for something like the first model, and I can see why: they want me to have a balanced life, to learn and grow and be at peace with myself and the world, in a holistic, happy and healthy way.

But then, none of my friends have conquered Persia.

Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of each model:

Sorry Alexander, but I gotta give it to Theory 1: The idea of life as a story appeals to me, and navigating between plots seems necessarily prior to dialing in on any one in particular. Or maybe I lack the soul of a conqueror—I want to be happy and take other people into account and have balance and lessons and beautiful moments.

Unless.

There are times when a particular plot burns with aliveness. When other plots recede, and nothing seems more important than the goal. In those situations, we arm ourselves with Theory 2. Amplify the aliveness, torch plan B’s, and make our goal our universe, at least for the moment.

Theory 1 remains the meta theory. But Theory 2 is not to be discounted.

Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and all that.

Great read! Some things that came up:

There might be something like an efficiency-resiliency tradeoff at play here, where we take efficiency to mean intentionally solidifying one (presumably highly relevant) frame/orientation/action protocol and take resiliency to mean intentionally contextualizing, ie simultaneously holding various frames/etc. The former being in service of sharp well-defined scoping that affords clear thinking and effective intent-outcome alignment, the latter in service of preserving relevance and meaning along the way. (There's a dope alignment with/orientation towards the notions of correspondence vs lived truth with these too, which you hit on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e1SLQC7IoUg)

Words; the interesting bit being that, at least where I ran into the efficiency-resiliency tradeoff grammar - AFTMC - they were framed as poles that a system dynamically moves between in exploit-explore fashion. Dynamic entailing notions like right relationship and attunement, rather than a global policy.

Could it be that Theory 1 fits in with the Infinite Game, i.e. the goal is to keep on playing, and Theory 2 is the Finite Game (goal is to win at all costs)?